(From Daniel Schell’s book : “MySpace”)

1.1 Introduction to tuning families

The number of different tunings in usage today has increased and offers to the player many solutions adapted to his style. In order to describe fully a tuning you have to consider the following elements :

1. The tuning is said to be uniform in fourths (or fifths) if the interval between the strings is only fourths (or fifths). Sometimes the tuning is not uniform, like on the Spanish or the Crafty guitar.

2. The tiptar has one or two playing regions. The guitar has only one region.

3. If it has two regions : Tuning of the melody side or of the bass side.

4. ” : The hands are crossed or uncrossed on the board.

5. ” : The hands play parallel or mirrored.

1.1.1 The « tuning word »

In order to describe a tuning we shall use a « word » : the tuning word. The first example we shall give is « 1<5_mel_4ths_RH // 5_bass_5ths_LH > 10 » seen from the player.

To read this « tuning word », you have first to think that you see your tap-guitar from behind, that is as you actually play it. This is the reason why I write « seen from the player ». In full words this would mean : 5 melody strings, tuned in 4ths ascending towards the left situated string#1, played with the Right Hand/ AND / 5 bass strings ascending in fifths towards the right situated string #10, played with the Left Hand.

The first figure you see is a 1. This is the number of the string #1, exactly as on the classical guitar.

After that you see 5_Mel_4ths_RH, which means 5 melody strings in fourths played by the Right Hand. The sign 1< , means that that the 5 melody strings in fourths ascend towards the left in direction of string # 1.

The other side reads as 5 bass strings tuned in fifths, played by the Left Hand, and the sign >10 means ascending towards the right situated string #10.

1.1.2 Families of tuning intervals

1.1.2.1 ONE-REGION BOARDS

– This type of board has only one playing region, like on the classical guitar.

– Strings ascend usually to the left of the player.

– Both hands play on the same region.

1.1.2.2 TWO-REGIONS BOARDS

– The board is divided into two regions. (or the tiptar has two necks).

– Each region is either in fourths or in fifths.

– One hand plays one region, but that is not a rule.

Table 1-1 The four arrangements of a two regions board

| bass | melody |

| fourths | fourths |

| fourths | fifths |

| fifths | fourths |

| fifths | fifths |

If we account for separate bass and melody tuning, we find four possible tuning super-families (see). One can see that the two families fifths-fifths and fourths-fourths are reflective, in other words, both sides require identical hand motions. On the other hand, the fifths-fourths and fourths-fifths tunings are not reflective: both sides require different hand motion.

1.1.3 Crossed hands – uncrossed hands tunings

Suppose you see your board from behind, as seen from the player. If you play with your right hand on the left side of the board, and your left hand on the right side, then you play « crossed hands ». You are in the family « 1_RH // LH_10 ». On the contrary, if you play with each hand on their respective sides then you play « uncrossed hands » and belong to the family « 1_LH // RH_10 ».

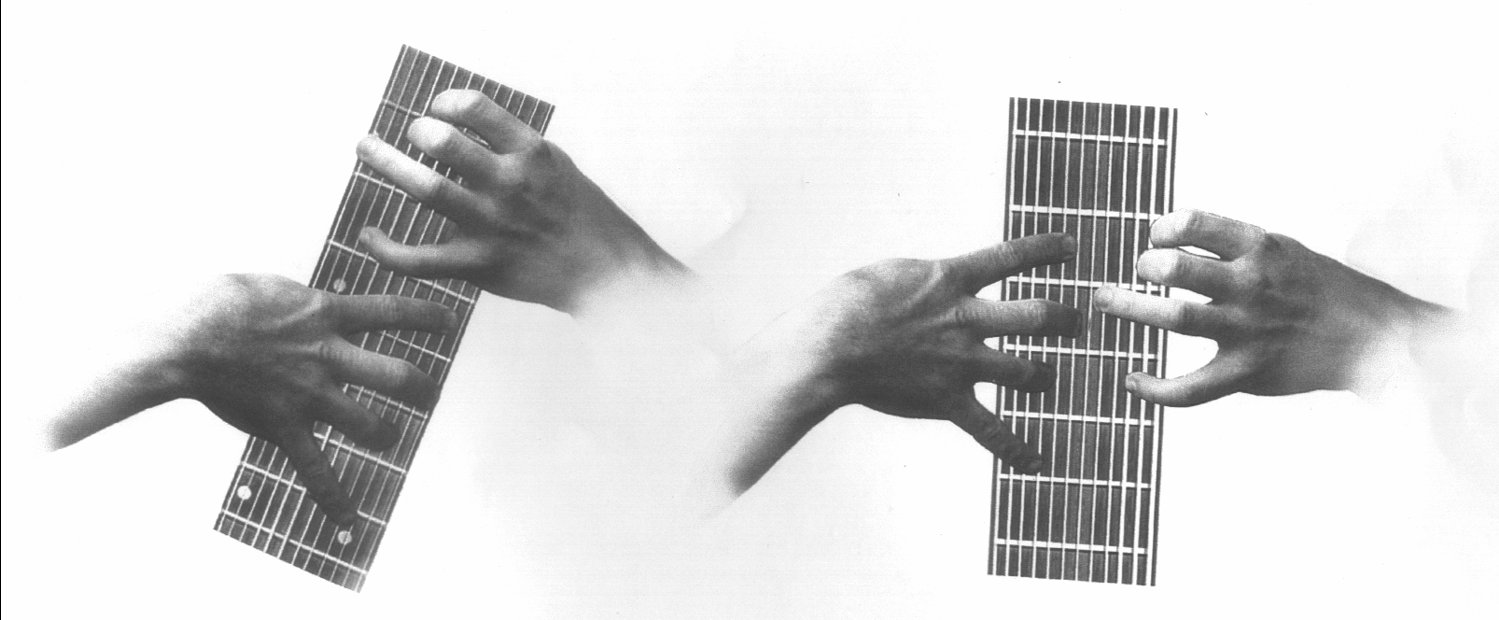

Figure 1-1 On the left, the playing with crossed hands. On the right, playing with uncrossed hands. Advantage of this last position : The hands do not interfere with each other in their vertical movements. (Drawing by Paul Catteau)

1.1.4 Mirrored hands, parallel hands

Our hands show symmetry, they are ‘mirrored’ . Suppose you wish to play a given pattern with both hands, say C-F-G-c from FIGURE 1-2. What is the natural way to play it? The ‘mirrored’ option, says that the patterns should be mirrored like the hands. In other words, the tuning should be mirrored. The author of the present book believes in this option. This is the ‘accordion’ effect: When you play an identical pattern on both sides, your hands go both in mirrored directions.

If you come from the guitar world, and wish to play two times guitar. Then you believe in the ‘parallel’ playing. The ‘parallel’ option says that the patterns should be parallel unlike the hands. This is the ‘piano’ effect: When you play an identical pattern on both sides, your hands go both in parallel directions.

1.1.5 A Quick guide: Which tuning should I play?

You want one region playing.

You wish to tap on an ordinary guitar ?1.2.1

You wish to extend the possibilities of the guitar to 8-str-? 1.2.2.1

You are a Crafty fan, and you do not wish to play the classical lines-? 1.2.2.2

You want two-regions playing.

You wish to read music with both hands and be able to play bass lines:

you don’t know which bass to choose?

You play mostly chords, you like the sound of open fifths in your accompaniment

Fifths-fourths, crossed hands?1.3.2.2

Fifths-fourths, uncrossed hands?1.3.3

Choose a tuning with the bass in fourths?

You are attached to your old guitar habits and want a melody upon it:

You like the idea of parallel uncrossed hands?1.3.1.5.1

You like the idea of parallel crossed hands?1.3.1.5.2

You like the idea of mirrored uncrossed hands?(bass in middle)1.3.1.3

You have no special guitar habits (Hell with these old habits!):

You like the idea of mirrored uncrossed hands (bass on sides)?1.3.1.2

You are an ex-Chapman tuning player AND:

You wish to go for uncrossed fourths-fourths: ?1.3.1.2

Not much time, a quick try to crossed fourths-fourths: ?1.3.1.4

You wish to play two-regions ‘crafty’ like:

Pure crafty? 1.5.1.1

‘Best of both worlds’ ?1.5.2

1.2 Boards with one region

| Table 1-2 tuning word for the various one-region tunings | |

| Type | Tuning Word, Intervals seen from the player |

| Bass 4 str. | #1<4,4,4,4<#4 |

| Spanish Guitar | #1<4,3,4,4,4,4<#6 |

| Guitar in fourths | #1<6x(4)<#6 |

| 8 strings in fourths | #1<8x(4)<#8 |

| 8 strings Crafty | #1<2,3,5,5,5,5,5,5<#8 |

1.2.1 Tapping on the ordinary classical electric guitar and bass guitar

A recent example is the Spanish Jesus Aunion. He plays a normal instrument , but detuned a second lower . The action is reasonably low. His technique involves tapping mixed with various techniques as cutting on open strings, tap chords, strumming, rasgueado, slapping. The sound is overall very ‘open’ and resonant and the playing involves rhythm and dynamics. Consult also the discography of the works of the Belgian guitar player Pierre Driesmans and the French Serge Pesce, who have both introduced interesting guitar techniques.

| Table 1-3: Jesus Aunion’s Spanish guitar tuning | ||||||

| String Nbr | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Open Pitch | D1 | G1 | C2 | F2 | A2 | D3 |

| Gauges | .054 | .036 | .026 | .017 | .013 | .010 |

String number seen from the audience

Similarly, there has been attempts to include tapping on the ordinary bass guitar. Olivier Verschueren has presented recently (2000) compositions including tapping, mixed with effects.

Surprisingly, there has been relatively few attempts to play on ordinary guitars tuned all in fourths. This seems to be the domain of dedicated ‘tiptar’ players.

1.2.2 The 8-strings tiptars

These are dedicated instruments, specifically built for tapping. Players of this type of instrument use the alternating-two-hands-on-one side method rather than the separate hands per side, in usage on the 2-regions tiptars. Frank Jolliffe says ” It should be noted that players of the 8-string touchstyle guitars incorporate both crossed and uncrossed hand positions as well as something I call the “linear hands”. This position has the hands moving in a leapfrogging fashion, over the top of one another, along the same or adjacent strings, while going up and down the fretboard. ” In “Touchstyle Quarterly” Vol 5, Number 2, April 1999. Notice that this type of linear playing can also be used on each or both regions of a two-region instrument.

There are mostly two types of tuning: In fourths or in Crafty fifths.

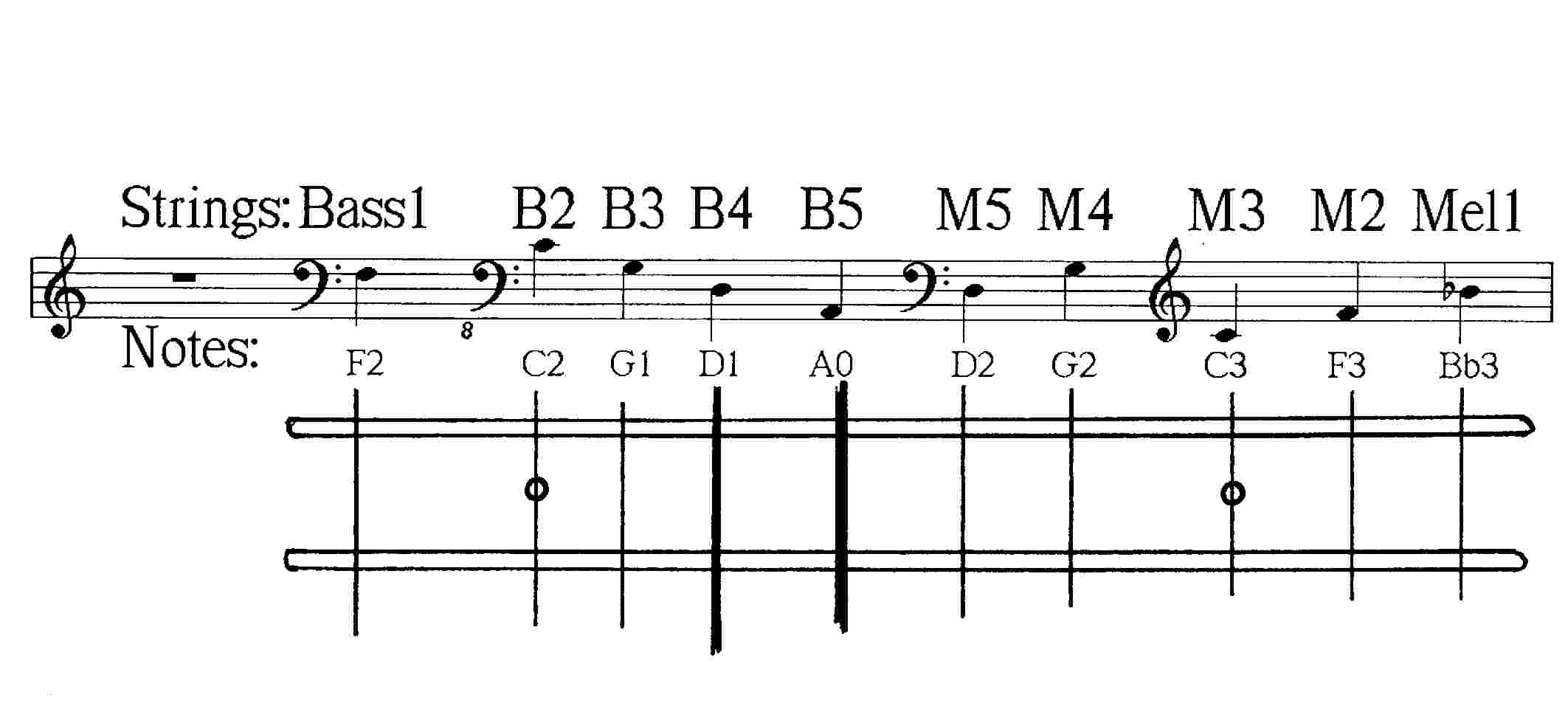

1.2.2.1 THE 8-STRINGS TIPTAR IN FOURTHS

The 8-str. tap-guitar can be tuned all in fourths and in one region. The tuning word is simply ” 1<8_4ths<8″ seen from the player. Some manufacturers consider that the tuning in B is the standard. Recently, Paul Mimlitsch and Ray Ashley have chosen to tune from low Eb (1999).

.

| Table 1-4 The 8-str. all in fourths tuned first from low B-1, second from Eb0 | ||||||||

| String | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Pitch (open) | B-1 | E0 | A0 | D1 | G1 | C2 | F2 | Bb2 |

| Gauge | .106/.125 | .100 | .080 | .060 | .040 | .025 | .016 | .011 |

| Pitch (open) | Eb0 | Ab0 | Db1 | Gb1 | B1 | E2 | A2 | D3 |

| Gauge | .100 | .080 | .060 | .040 | .025 | .016 | .011 | .009 |

1.2.2.2 THE 8-STRINGS TIPTAR IN CRAFTY FIFTHS

Some players play a fifths tuning variant, that reflects their experience as “Crafty” guitarists. For the melody strings they adopted a tuning derived from Robert Fripp´s “New Standard Tuning” ,On this instrument, 6 strings are in fifths. On the top of that add a third then a second. This tuning, which is not uniform, is used amongst others by Markus Reuter and Kuno Wagner. The strings are tuned as follows

| Table 1-5 The 8-str Crafty tuning, with 6 fifths, one third, then a second. | ||||||||

| string | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| notes (open) | Bb-1 | F0 | C1 | G1 | D2 | A2 | C3 | D3 |

| String diam. | .100/.105 | .080 | .060 | .040 | .020/.016 | .012 | .011 | .010/.009 |

1.3 Boards with two regions

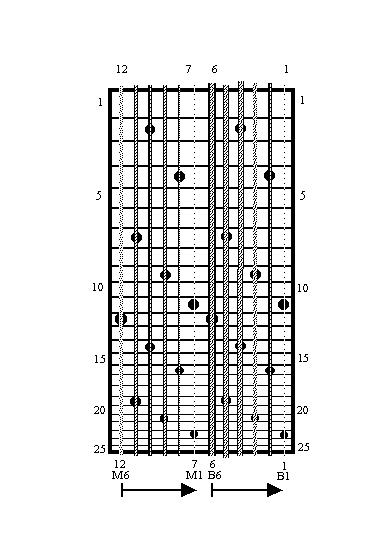

This section covers the tapping boards divided into two regions. Usually the total number of strings ranges from 10 to 14. The regions are mainly tuned in fourths-fourths, fifths-fourths or fifths-fifths.

1.3.1 Tunings in fourths-fourths

1.3.1.1 THE GRAPHIC SPACE OF THE 4-4 INSTRUMENT

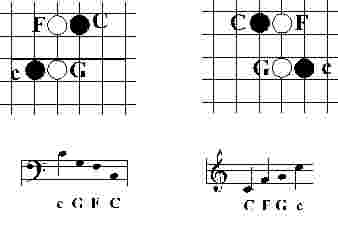

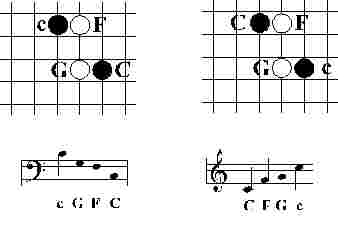

The simple idea behind 4-4 tunings is that identical patterns are played identically on both sides (see FIGURE 1-2). The 4-4 tunings can be divided into mirrored or parallel. Suppose that we take a mirrored tuning, then in order to represent the invariant motif C-F-G-c on the bass side, we simply need to take the sign C-F-G-c of the melody side and to mirror it symmetrically. The bass playing is simply the mirroring of the melody playing.

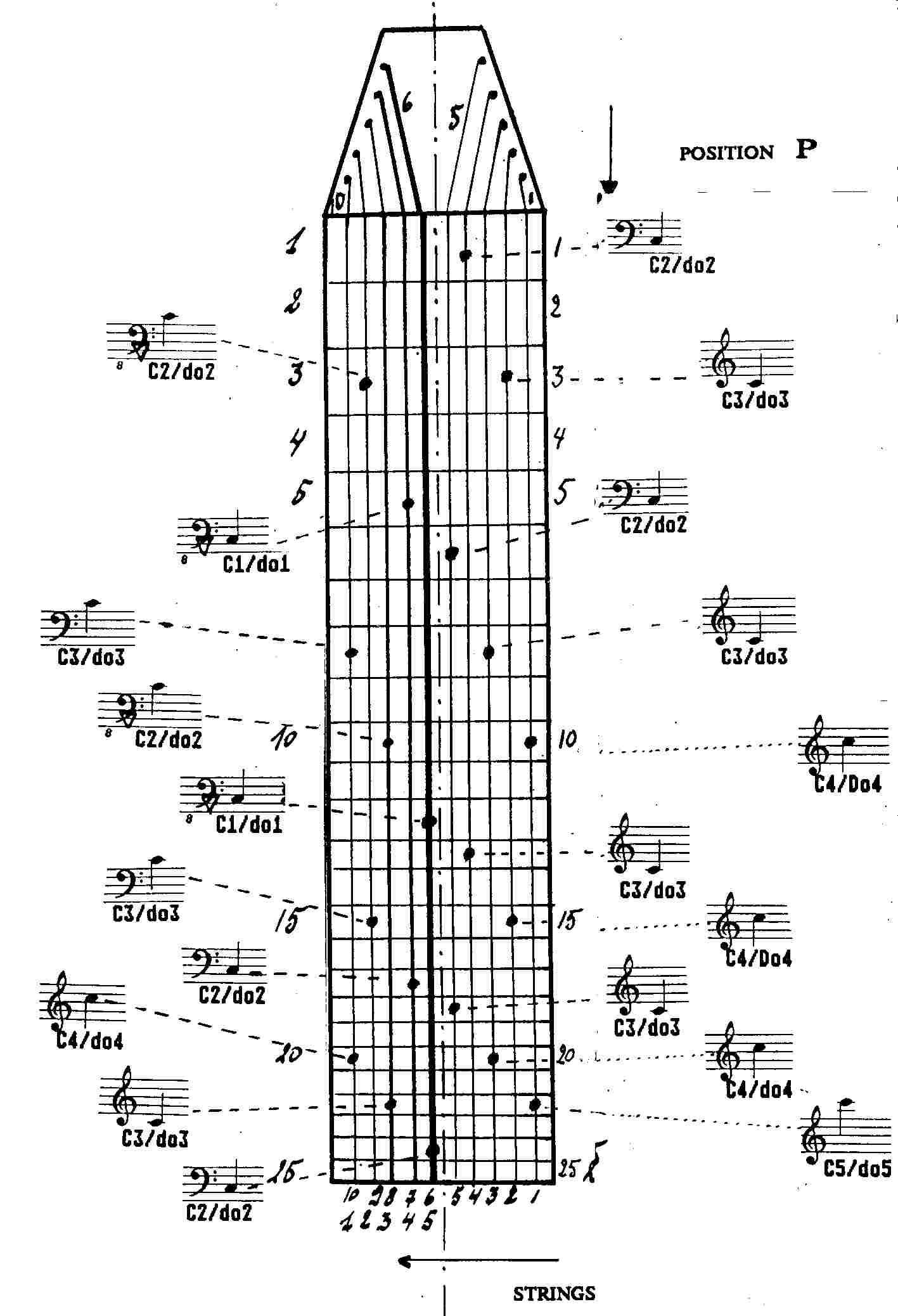

FIGURE 1-2 Symmetry between left and right hand: The melody space, in fourths, is represented on the right; the bass, also in fourths, on the left.

As they are symmetrical, the signs C-F-G-c reflect each other, and so does the playing. The hands and the motives show the same symmetry.

1.3.1.2 UNCROSSED MIRRORED FOURTHS, BASS ON THE SIDES

Tuning word: «1>6_bass_4ths_LH // 6_mel_4ths_RH <12 » seen from the player.

Tuning word: «1>6_bass_4ths_LH // 6_mel_4ths_RH <12 » seen from the player.

In this tuning, basses are on the side of the board, while trebles are in the middle. You play ascending scales by bringing hands closer to each other. Advantage of the trebles grouped in the middle: You can see clearly the melodic notes and the higher extensions of the harmony.

Other advantage: For those who, like me, have started to play along Chapman « Free Hands » method, and have done so for a few years, it would be too late to adopt the Daiss tuning, because that would involve a change of all their mental mechanisms. For instance to play an ascending scale in the melody, they move their right hand to their left side. Wolfgang does it by moving his right hand towards his right side. That is quite something to modify if you have been practising for years. Those might better adopt this tuning that I play now, and which was suggested to me by Wolfgang Daiss .

One is getting easily used to the bass strings on the side This has the advantage that the high strings of both sides are grouped in the centre of the board and therefore very visible. It is for instance very convenient for players who like to find sophisticated harmonies. Your instrument should allow for some space on the side of the bass string.

| Table 1-6 The 12-strings mirrored 4th /4th uncrossed hands. Two types of gauges are given, normal and heavy | ||||||||||||

| 12 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Bass/Melody | B6 | B5 | MB4 | MB3 | M2 | M1 | B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 | B5 | B6 |

| row 9: | A1 | D2 | G2 | C3 | F3 | Bb3 | Bb2 | F2 | C2 | G1 | D1 | A0 |

| open (row 0) | C1 | F1 | Bb1 | Eb2 | Ab2 | Db3 | Db2 | Ab1 | Eb1 | Bb0 | F0 | C0 |

| Gauge ” normal | .034 | .025 | .016 | .012 | .009 | .008 | .013 | .022 | .028 | .044 | .065 | .092 |

| Diameter: mm | .87 | .64 | .41 | .31 | .23 | .20 | .33 | .55 | .71 | 1.12 | 1.66 | 2.34 |

| Gauge ” heavy | ||||||||||||

| Diam mm | ||||||||||||

1.3.1.3 UNCROSSED MIRRORED FOURTHS, BASS IN THE MIDDLE

Around 1990, Wolfgang Daiss, came on with what might be the best guitar-reader approach. A mirrored version of the Daiss tuning, represented on Figure 1-4, looks like «1< 6_bass_4ths_LH // 6_mel_4ths_RH > 12 » seen from the player. Daiss has always been a professional guitar and lute player. He has to work in ensemble, under the direction of a chef, where a heavy demand is made on the reading ability. He has to change frequently from instrument and has to keep some constants whatever the instrument he plays. Therefore he thought : « I shall keep my left hand as if it was playing the guitar, and add a symmetrical right hand to it, and there you have the Daiss tuning. With this tuning, Wolfgang has recently created the « tiptar » part in my opera « Hygiène de l’Assassin ». I would personally recommend this tuning to all the new players starting from scratch. It has three advantages : the bass strings are in the middle, the tuning is in the fourths-fourths family, the hands are uncrossed.

| Table 1-7 The Daiss tuning for a twelve strings instrument | ||||||||||||

| String | 12 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Bas/Mel | M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | B6 | B5 | B4 | B3 | B2 | B1 |

| Pitch open | Eb3 | Bb2 | F2 | C2 | G1 | D1 | B-1 | E0 | A0 | D1 | G1 | C2 |

| gauge “ | .009 | .011 | .013 | .025 | .035 | .040 | .125 | .080 | .060 | .045 | .030 | .016 |

Daiss has some ‘guitarist’ thoughts about this tuning:

6. This tuning is ‘mirrored’ like the Schell tuning. However the axe of symmetry is different. In some cases, the hands playing octave apart parallel melodies are two frets apart, a disposition he likes.

7. String #5 is analogue, one octave lower, to string #6 of the classical guitar (Remember: Daiss plays both instruments currently)

8. String #3 is identical to #7; #2 to #8; #1 to #9, which allows some identical patterns on both sides. One of these patterns is the following: On row 2, bass side, Wolfgang sees E (on string #3), A (on #2), D (on #1). That disposition of notes is identical to the open guitar. The same pattern is mirrored, on the melody side on strings #7, #8 and #9.

9.

Today Wolfgang Daiss plays a 14 str tiptar. The tuning is given in Table 1-8

| Table 1-8 The Daiss tuning for a fourteen strings instrument | ||||||||||||||

| String | 14 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Bas/Mel | M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | B7 | B6 | B5 | B4 | B3 | B2 | B1 |

| Pitch open | Eb3 | Bb2 | F2 | C2 | G1 | D1 | A0 | B-1 | E0 | A0 | D1 | G1 | C2 | F2 |

| gauge “ | .009 | .011 | .013 | .016 | .025 | .035 | .040 | .125 | .080 | .060 | .045 | .030 | .016 | .013 |

1.3.1.4 CROSSED MIRRORED FOURTHS, BASS IN THE MIDDLE

Tuning word is «1< 6_mel_4ths_RH // 6_bass_4ths_LH > 12 » seen from the player

In this system, the lowest string acts as an axis of symmetry. This tuning is easy to adapt for people who play the Chapman tuning and wish to try the bass in fourths, just by re-tuning a few strings.

During the summer of 1985, I was still playing the Chapman tuning. I decided that, as a music reader, I could not go anymore with the fifth-fourth tuning, which I found too complicated, especially as I wanted to read music and play « bass lines » in the sense of Bach. And so, on a suggestion from Jim Lampi, I tuned my bass in fourths, This tuning became known as the « mirrored fourths » tuning.

| string: | ||||||||||||

| Bass/Melody | ||||||||||||

| row 9: | ||||||||||||

| open (row 0) | ||||||||||||

| gauge ” (light) | ||||||||||||

| diameter: mm | ||||||||||||

| gauge ” (heavy) | ||||||||||||

| diameter: mm | ||||||||||||

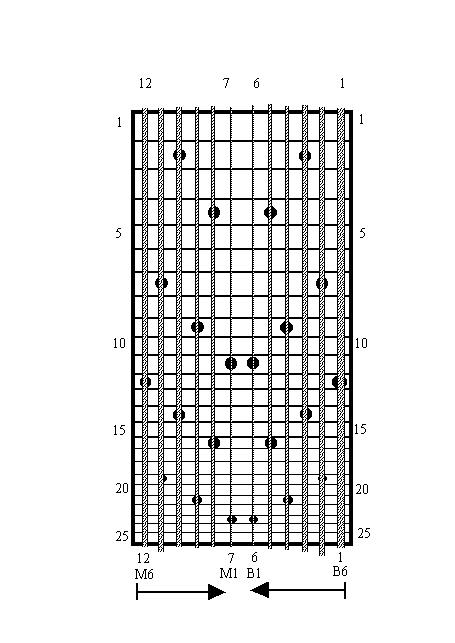

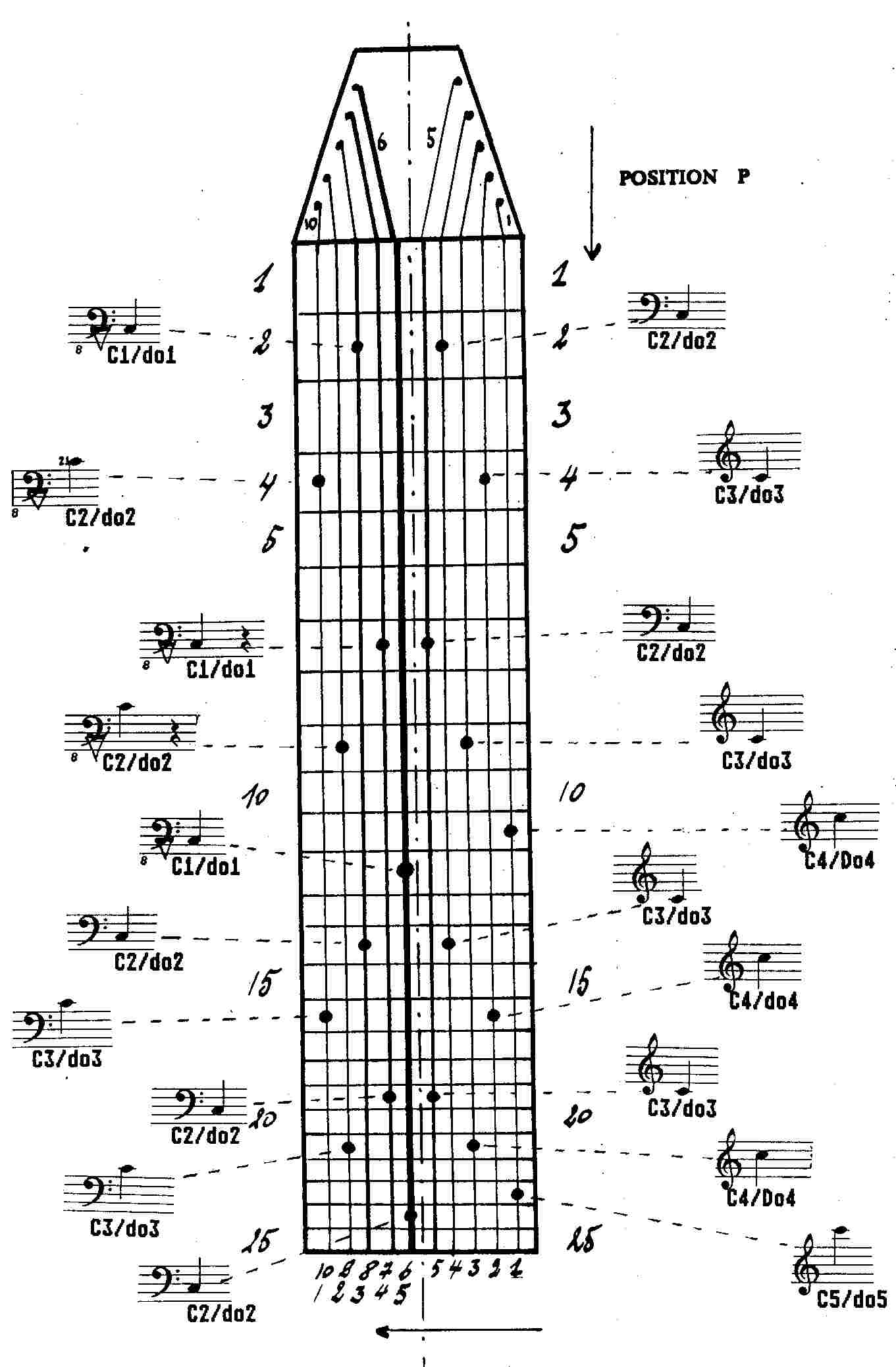

Figure 1-3 Tuning 10 strings in mirrored fourths, crossed hands. Notes at row 9.

Figure 1-4 Tuning 10 strings in mirrored fourths, crossed hands. The setting is analogue to the Chapman tuning but with the bass in fourths instead of fifths.

We give in the variant of the same tuning for a ten strings instrument.

Tuning word; « 1<5_bass_4ths_LH // 5_mel_4ths_RH>10 » seen from the player.

| string: | |||||||||||

| Bass/Melody | |||||||||||

| pitch row 9 | |||||||||||

| pitch open(row 0) | |||||||||||

| gauge ” (light) | |||||||||||

| diameter mm | |||||||||||

| gauge ” (heavy) | |||||||||||

| diameter mm | |||||||||||

1.3.1.5 PARALLEL FOURTHS

In this family, both sides are tuned in fourths and both are ascending in the same direction towards string 1. The hands move both in a parallel guitar-like fashion. The author believes that this is somehow anti-natural, given the symmetric disposition of the hands. However, users of this tuning like its ‘double-guitar feeling’

1.3.1.5.1 Uncrossed parallel fourths

Tuning Word: «1<6_bass_4ths_LH//6_mel_4ths_RH<12» seen from the player.

This tuning is played, for instance, by Jim Wright and Olivier Verschueren (2000) .

The bass string #6 is then in the middle and can bring some trouble playing string #7, the highest of the melody. The construction of the instrument should allow for some space between strings #7 and string #6.If you decide to play this tuning, take care to order an instrument with enough space between Melody 6 strings ( the highest on your RH) and Bass 1 string ( the lowest and thickest of of your LH). The experience shows that B6 can be an obstacle while reaching M1

1.3.1.5.2 Crossed parallel fourths

The tuning word is «1< 6_mel_4ths_RH // 6_bass_4ths_LH // < 12 » seen from the player.

If you take the tuning represented in

Figure 1-8 and flip the bass and melody side, you will have the bass side on the left and the melody on the right. And If you play the bass with the left hand, this means that the hands will be crossed, a serious disadvantage following the author of the present book. This tuning has been adopted by several American players like Teed Rockwell (2000), Traktor Topaz (1997) and the Japanese player Katsu (2001). We give in Table 1-11, the tuning used by Traktor Topaz

| Table 1-11 Crossed hands parallel fourths used by Traktor Topaz on his Megatar ™ | ||||||||||||

| String # | 12 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Bass/Mel | B6 | B5 | B4 | B3 | B2 | B1 | M6 | M5 | M4 | M3 | M2 | M1 |

| Open at row 0 | B-1 | E0 | A0 | D1 | G1 | C2 | C#1 | F#1 | B1 | E2 | A2 | D3 |

| Gauge “ | .100 | .085 | .065 | .050 | .035 | .025 | .040 | .029 | .016 | .012 | .011 | .009 |

1.3.2 Tunings in fifths-fourths

1.3.2.1 THE GRAPHIC SPACE OF THE 5TH-4TH INSTRUMENT

Let us represent the sign C-F-G-c in this system. This time we observe a similarity with the sign C-F-G-c of the melody side: both signs look the same. But this similarity is an octave apart, unfortunately, because the player sees c-F-G-C and not C-F-G-c.

An amusing phenomenon happened: The player sees fourths but hears fifths. When playing fifths towards him, he sees inverted fifths, that means fourths. But these are virtual fourths, and here is their effect: on the left c-F-G-C (fifths), the notes have kept their name, except for their octave! This has the following consequence: playing an identical pattern on both hands will produce identical notes but with an octave jump at each string change. This is of high visual facility, but musically useless.

There is an historical origin to the tuning in fifths: When Emmett Chapman was experimenting with ordinary guitars, he once had the idea of turning his guitar head down (this is genius!). What he saw then is analogous – but not identical – to the actual string set-up. Further reasons for adopting this tuning are really reflecting Chapman’s personality as a musician: he is an improviser and needs therefore the roots and fifths of his chords more than diatonic bass lines; he is a creator of “objets musicaux” – “musical objects”, to quote Pierre Schaeffer – probably willing to pay more debts to Jimi Hendrix than to the written musical tradition.

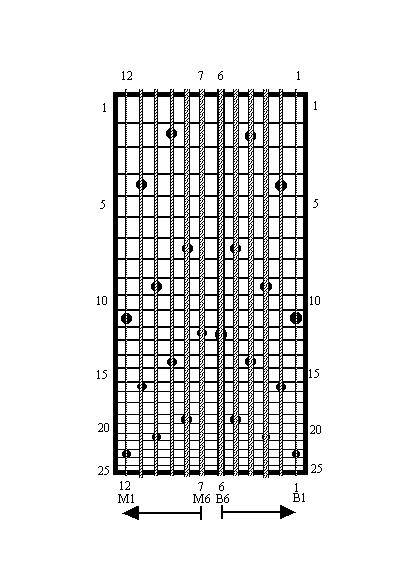

In short, for an identical pattern, the playing of both hands is different, which is difficult. However there is a little trick (see Figure 1-9) which facilitates the visualisation of the board.

Figure 1-5 The relationship between left and right hand on the 5-4 instrument : The melody space of fourths is represented on the right side, while the bass space of fifths is on the left. It looks like the sign is transposed from the right to the left and remains identical! Not exactly: the name of the notes do not change, but their octaves do. An inversion has occurred. The player sees fourths but hears fifths.

1.3.2.2 THE CHAPMAN CROSSED FIFTHS-FOURTHS TUNING

Emmett Chapman has created a tap-guitar (manufactured by Stick Enterprises USA as « Stick » TM) tuned with the bass in fifths, and the melody in fourths, played with the hands crossed, known as the Chapman Standard tuning. In our « word » it would look like « 1<5_mel_4ths_RH // 5_bass_5ths_LH > 10 » seen from the player

“Emmett Chapman first used this tuning on guitar in 1967 (with lowest three strings flipped to backward 5ths), and in 1969 on his guitar using his unique tapping method. The “so called Standard tuning” you refer to is the “standard Stick® tuning”, for which Emmett should rightly be credited.” ! (A letter from Mrs Yuta Chapman to the Author) And so Mr Chapman came up with an instrument made specially for the tapping technique, with a board divided in two, one for each hand, a melody side tuned entirely in fourths (not one hidden third somewhere like in the Spanish guitar). However, the tuning contained two apparently weird features: A bass in fifths, and a crossed-hands technique.

1.3.2.2.1 Tuning the instrument in crossed hands 5th-4th

The 5th-4th instrument has the following tuning: bass in fifths, melody in fourths. The tuning word is « 1<5_Mel_4ths_RH // 5_Mel_5ths_LH>10 » seen from the player. In this system, the bass strings (6 to 10) are tuned in fifths towards the player. The lowest string acts therefore as an axis of symmetry (see FIGURE 2-2).

This tuning is not the easiest to play bass lines but it is a favourite for those who like to play open chords accompaniment with the left hand.

| Table 1-12 Standard Chapman 10-str: Pitches / diameters (recommended by the author) | ||||||||||

| string: | ||||||||||

| Bass/Melody | ||||||||||

| notes at row 5 | ||||||||||

| notes open (row 0) | ||||||||||

| Gauge Inch (light) | ||||||||||

| diameter mm | ||||||||||

| Gauge ” (heavy) | ||||||||||

| diameter mm | ||||||||||

Notice also that this tuning is not mirrored. This can be a slight disadvantage: as seen by the player, all the strings are separated by a virtual fourth, except between middle strings (6 and 5). This space is therefore not entirely coherent. It can be seen that the lines of the C-dots are broken. This is a problem mainly in the readability of the board. Emmett Chapman is conscious of this, but he prefers his tuning, as it allows him special chord positions in the left hand on both bass and melody parts of the board. A number of “barré” positions are idiomatic to his style.

Figure 1-6 The Chapman tuning for a 10 strings instrument seen from the audience The pattern of notes is represented at row 5. Melody is in fourths ascending to the right, bass is in fifths ascending to the left. Playing is done with crossed-hands.

Figure 1-7 The bass in fifths-melody in fourths 10 strings tuning invented and used by

Emmett Chapman

1.3.2.2.2 The 12 strings Chapman tunings

Around 1990, Mr Chapman started to manufacture instruments with 12 strings instead of 10. The tendency today goes in favour of these 12-strings instruments which are easier to play.

The strings can be divided into two groups of 5 bass-7 melody , or simply 6-6. The additional strings are very welcome and will involve usually one or more lower strings on the melody side and a higher string on the bass side. The additional strings greatly facilitate the playing of difficult pieces. The bigger overlap between bass and melody register also offer new possibilities.

The table below shows the tuning of the 6/6 disposition of strings. The gauges are given for two alternatives: medium or a heavy. The source for the normal set comes from the author. The source for the heavy set comes from Frank Jolliffe’s Power Tapper specially designed for the Warr Guitar.

| Table 1-13 Chapman 12-str tuning: Pitches of the strings and diameters | |||||||||||||

| string: | |||||||||||||

| Bas/Mel | |||||||||||||

| notes row 5 | |||||||||||||

| notes row 0 | |||||||||||||

| Gauge ” med | |||||||||||||

| Diam. mm | |||||||||||||

| Gauge ” heavy | |||||||||||||

| diam mm | |||||||||||||

1.3.2.2.3 Baritone, and transposed variants of the Chapman tuning

Emmett Chapman has brought up many tuning variants belonging to the fifths-fourths family. These are mainly with lower pitches and thicker strings. The playing method is not changed, although the sound is different. To quote Chapman: “They are fuller and thicker sounding, giving the instrument rhythmic punch and strength”. (Stick Wire, Aug. 91). The table list the pitches of the open strings. The numbers next to the pitches indicate the octaves.

| Table 1-14- the Baritone tuning. Pitches of the open strings | ||||||||||

| string | ||||||||||

| notes | ||||||||||

On the Baritone tuning , the melody strings are a fourth lower than on the Standard and the bass strings are up a whole tone.

1.3.3 The Carpentier uncrossed fifths-fourths tunings

Tuning word : «1> 6_bass_5ths_LH // 6_mel_4ths_RH <12 » seen from the player.

Thierry Carpentier, who studied and played accordion, decided to uncross his hands in september1989. During the E-Tap Seminar of July 1991, I saw Kuno Wagner playing a tiptar with uncrossed hands on a similar tuning.

These tunings have inherited from the fifths-fourths concept of Emmett Chapman, however the hands are uncrossed. The bass strings are on the sides and the tuning ascend towards the treble strings situated in the middle. A definitive advantage is that the hands do not interfere anymore with each other and can have free access to the entire board. For instance they could play at the same horizontal level.

1.4 Which tuning to choose: 4-4 or 5-4?

The tuning of the bass in fourths is certainly the most logical, and it is the one chosen by the author of this book. There is yet another matter to discuss, and here are the essential elements:

1.4.1 Bass in fifths

. Advantages:

In the beginning, the playing looks easy for simple bass lines of the C-F-G-c family. Simple repetitive bass patterns on roots and fifths can be played without problems (Rock, Samba). There is a larger span in notes: 2 octaves and one major third on a single row (28 half tones). The bass in fourths, in comparison, has a span of one octave and one minor sixth (20 half-tones). This is the distinctive quality of the tuning in fifths that, to quote Emmett Chapman “offers some big advan-tages in two-handed playing.”

The left hand can accompany the right with simple wide-intervals chords that are not available on standard bass (the bass in fourths).

Unique bass lines and patterns fall easily on the fingers.

The left hand can easily grasp 2 1/2 octave over a span of three frets on the bass strings alone.

Disadvantages:

The bass is then tuned as a cello. This makes playing diatonic bass lines difficult because it involves permanent change of position. The “repertoire” of the double-bass is practically excluded. Also you can forget about reading with both hands.

The fourths melody-hand play does not obey the same graphic rules as the fifths bass-hand play. This produces extreme, if not insuperable, difficulty in the execution of two simultaneous melodies.

Emmett Chapman tells us in “Free Hands”: “Tuning the bass in fifths, … some intervals are easier to reach such as fifths…. Other intervals need a long reach like all scale playing. The natural language of the bass in fifths takes your fingers into a more vertical approach to the bass lines, with larger interval leaps falling more easily into the finger technique. Bass tuned in fourths, on the other hand, brings you into a more melodic language, like that of jazz walking bass or the bass counter-point of baroque” (lesson 10). “Keep in mind that scales are harder to play on Stick (he means in fifths) bass and larger intervals are easier” (lesson 11).

1.4.2 Bass in fourths

Advantages:

The playing is graphically identical to a bass guitar seen in a mirror and graphically identical for both hands, and therefore easier. All melodic lines are possible. There is access to the interval of a second in position.

Disadvantages:

There is access to a reduced number of notes (28% less than in fifths for an identical po-sition). This problem is solved with an instrument with 6 strings on the bass side. (see1.3.2.2.2).

The tuning of the bass in fourths is the one I personally recommend for its simplicity. Though having played in fifths for 5 years it just took me a month to learn to play in fourths. As I always played according to the C-dots, the process was easy. When I tuned the bass in fourths, I changed the positions of the C-dots and my hands automatically followed.

1.4.3 How to go from the 5-4 to the 4-4 instrument

It is important to notice that they are not different instruments. You only have to retune a few strings on the bass side. In order to do this choose the tuning explained in section 1.3.1.4. To go from one to the other is very simple: retune strings #7 to #10 (Bass #4 to #1) in fourths. That’s all. Strings #1 to #6 (melody #1 to #5 and Bass #5) remain unchanged.

1.5 Other Tuning variants

In this section we will discover other tuning variants that can be found in the three families: fifths-fourths, fifths-fifths and fourths-fourths.

Technical limits:

One technical remark is valid for all the existing families: today, the first string cannot be thinner than .007 inches (0.17 mm). The upper note Eb5 – reached on the first string, last fret, of the Chapman Tuning – seems to be the upper limit. Further tension of this string leads to frequent break.

The bass string of .092R inches (2.34 mm), on the other hand, is present on nearly all tiptars. The C# it produces on the first row of the neck is hardly perceptible as a pitch and therefore constitutes a natural lower limit. Nevertheless there are players who tune the bass section a whole tone lower than standard using heavier gauges.

1.5.1 The tunings in fifths-fifths

The tuning in fifths-fifths, like the fourths-fourths, offers the distinctive advantage of being reflective, as opposed to the fifths-fourths. It is reflective in the sense that the graphical play of both hands is symmetry-identical. The tuning in fifths-fifths should appeal to violin and cello players, who were educated with this space.

Its inconvenience was already discussed in:0: permanent change of position when playing diatonic lines.

1.5.1.1 THE “CRAFTY” FIFTHS-FIFTHS VARIANTS

Some players, as Trey Gunn, have adapted the crafty tuning to two-regions tiptars. Here is one of their open tunings:

| string | ||||||||||

| notes | ||||||||||

As you can see, the bass is tuned in fifths. One should observe that there is an interval of a third between the last two strings on the treble side This space is then no longer coherent, like a whole fifths space, and one should expect inconvenience in reading.

Recently, a family of players has added a second on top. With six strings, it would be C, G, D, A, C, D.

1.5.2 The Bowmer ‘best of both worlds’ tuning

Tuning word: “1>6 Bass 5ths LH (C0 G0 D1 A1 E3 B3) /// 6 Mel 4ths RH (D3 A2 E2 B1 F#1 C#1) < 12 ”

During the E-Tap Seminar 1999, Dave Bowmer developed with the help of Kuno Wagner, an interesting tuning combining the crafty world with the easyness of melody in fourths.

We quote his words (Email to the author September 1999) : ” I am taking your advice and changing today to uncrossed on my 12 string and reverting to 4ths in the melody in the RH on the RHS of the fret-board as seen from the player. I will retain 5ths in the bass to be able to do my crafty work, by tuning as follows I actually get a 7 string inverted crafty tuning in the bass side, good for the 2 handed combined mono style, as the interval between the 6th and 7th strings provides the minor 3rd on top of the 5ths as per crafty, while for stereo 2 hand independent playing I get 6 melody strings in 4ths and 6 bass in 5ths uncrossed – so quite a good solution for my special requirements with a single instrument I think.”

Here is the Bowmer’s tuning seen from the audience:

Table 1-16 The ‘best of both worlds’ tuning. It has uncrossed fifths in the bass, fourths in the melody. The M1 can serve as the ‘crafty’ third on top of the bass.

| String # | 12 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Bas/Mel | M6 | M5 | M4 | M3 | M2 | M1/B | B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 | B5 | B6 |

| Open pitch | C#1 | F#1 | B1 | E2 | A2 | D3 | B2 | E2 | A1 | D1 | G0 | C0 |

One will notice that string 7, tuned D3 is actually one third over B2. Therefore providing the third needed for stepping in the Crafty world. In the point of view of a crafty player, the tuning word could also be rewritten as: 1 > 7 bass 5ths (C0 G0 D1 A1 E3 B3 D3) /// 5 Mel 4ths RH ( A2 E2 B1 F#1 C#1 ) < 12

1.5.3 The experimental tunings

The tiptar is an ideal tool of experimentation for all kinds of new tunings. We may classify these tunings into two broad categories: Tonal tunings and coherent interval tunings.

The tonal tunings involve various intervals between strings. For instance, there will be two fourths, then a third, then another fourth. They often reflect a performer’s desire to facilitate the playing in one tonality, or just one song. (In analogy, the open guitar is an E-min tonal tuning.)

An interesting subclass or experiment is the micro-tonal tuning. Some strings are tuned a few cents up or down to simulate quarter-tones, acoustic or micro-intervals. With an electronic tuner, the author managed to reproduce approximately the Euclidean or Zarlino scales.

The coherent interval tunings are a family of logical spaces made entirely of one interval: the fourths-fourths and fifths-fifths tuning are of this sort. In terms of mathematics, we might call these spaces: map-pings of the Cartesian space. They are logical, without surprises.

The reader might also experiment with the following coherent tunings: all in tritones, all in sixths, all in thirds. In the coherent spaces, it is interesting to experiment with geometric figures: polygons of all sorts played on the coherent instrument also sound “polygonal”.